The Changing World of Work 5: "Human Robots" and High-Level Skills

April 17, 2015

A diploma by itself does not create value; only experiential skills create value.

While it is impossible to summarize the job market in a vast, dynamic economy, we can say that the key to any job is creating value. That can be anything from serving someone a plate of mac-and-cheese to fixing a decaying fence to feeding chickens to securing web servers to managing a complex project--the list is essentially endless.

The question is: how much value does the labor create? The value created, and the number of people who are able to do the same work, establishes the rate employers can afford to pay for that particular task/service.

As noted elsewhere in this series, work that can be commoditized has low value because it can be outsourced or replaced by software and machines. In cases where it is not tradable, i.e. it cannot be performed overseas, the value is limited by the profit margins of the service being provided and the number of people who can perform the work.

In many cases, for example, the fast food industry, workers are trained to become human robots, highly efficient at repeating the same tasks dozens of times per shift.

The severe limitation of human robot jobs is that they rarely offer much opportunity to learn a wide variety of skills--precisely what enables us to create more value with our labor.

Longtime correspondent Kevin K. describes how this lack of opportunity is a function of Corporate America, which demands every employee follow set procedures to homogenize the customer experience throughout the company and insure the product is the same everywhere in the market sector.

Small business, in contrast, allows for young employees to learn by doing a wider range of tasks and perhaps even experiment with products and placement. Here's Kevin's commentary:

On our way home yesterday we stopped for lunch at a Rubios (a Mexican chain with about 200 locations). I was telling my wife that the young people working for minimum wage at the sterile corporate Rubios today have a VERY different work experience than my friend Sean had working at the second Rubios in 1985 where he got to work side by side with founder Ralph Rubio.Looking around the mall, 100% of the stores were big chains with 100+ locations and corporate top-down management where just about anyone with an 8th grade education can do 90% of the jobs and people don't have any ability to do anything different or get creative.

When I worked in the local grocery store in High School I could put items where I thought they would sell best (we would keep track of this to see if say Bud Light sold faster after we moved it above the Coors Light closer to eye level, after I got down from the roof after adjusting the beer case HVAC unit to make it colder).

Today kids in retail have to put everything in the exact spot that the corporate marketing people tell them to put it (and would never be allowed to get on the roof and work on the HVAC system).

Correspondent David C. related the results of conversations he recently had with two young American engineers working for major companies in the U.S. The take-away reinforces one of the key points made earlier in this series: that creativity, communication and collaboration are as important as engineering skills in creating high value goods and services. Here is David's commentary:

Young Engineer #1's job (as I understand it) is to take what the people in "Business" want (to offer a new product, to mine the data for new opportunities, etc.) and

1. through his knowledge of the firm's technology databases and data structures say whether what is desired is even possible, or propose parallel alternatives, and

2. determine how a new set of programming instructions would be structured to work with existing systems and produce the desired output.The actual coding is off-shored to coders in India. He writes essentially zero code, despite being assigned previously to a COBOL-language mainframe system.

Young Engineer #2 noted that essentially everything being taught in Comp Sci classes in college is outmoded. He said that now there are entire libraries of open-source code available, and people doing a project simply have to organize the pieces, seeking out and copying "prior art" that is freely available to accomplish tasks of great complexity without reinventing the wheel for any of it.

I got the impression that while knowing how to write actual instructions and compile them may be useful base knowledge, it's simply not relevant to day-to-day work in the field.

Both of these explanations inform me that the basic skill needed is highly abstract, conceptual thinking, the ability to organize multiple elements into a coherent whole and to think through IN ADVANCE the series of intermediate results that combine into a final output.

Then add another necessary skill: interpersonal communication. Young Engineer #1 notes that foreign students in the US getting advanced degrees in STEM fields are wildly intelligent, but in his experience they simply can't connect with the "people in Business." The gulf between them is too wide, and so despite being fabulously intelligent and skilled, the overseas-educated engineers often can't deliver what the firm actually needs.

The overseas-educated engineers are often extremely bright and very skilled at the academics of engineering, but are often hamstrung by cultural variables that render them poor at problem-solving, especially when individual initiative and willingness to break convention are what's needed.

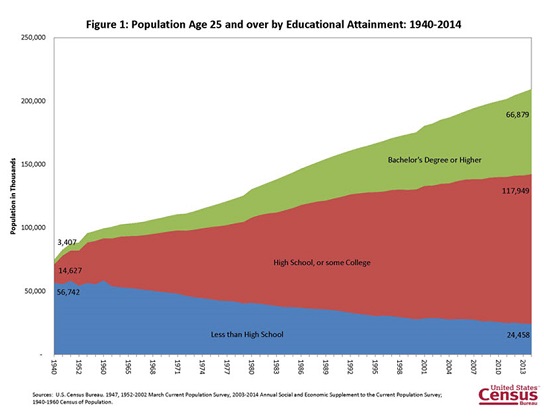

Kevin submitted a U.S. Census chart of the educational attainment of everyone 25 and older. His comment sheds light on one of the structural difficulties in creating high value: the number of college graduates exceeds the number of positions that create enough value to demand high wages. Kevin commented:

In the last 40 years the number of people over 25 without a HS diploma has been cut in half while the number of people over 25 with a college degree has more than doubled. The only problem (as you pointed out a while back when you said that having 10 people get PhDs in chemical engineering this year will not create 10 new jobs for chemical engineers this year) is that the number of jobs that "need" college degrees has not doubled.

A diploma by itself does not create value; only experiential skills create value. The more skills a person owns across a range of disciplines and trades--not just specialized skills but the professional skills of problem-solving and bringing out the best in others--the greater the opportunities for value creation and matching compensation.

NOTE: Contributions/subscriptions are acknowledged in the order received. Your name and email remain confidential and will not be given to any other individual, company or agency.

|

Thank you, Walter S. ($250), for your beyond-outrageously generous contribution to this site-- I am greatly honored by your steadfast support and readership. |