Bank Reserves and Loans: The Fed is Pushing On a String

The money multiplier effect no longer works.

As you (hopefully) know, we live in a fractional reserve banking system: if the bank is required to have $1 in cash reserves for every $10 in loans, it means the bank creates $10 of new money when it issues a $10 loan. When the $10 loan is paid off, that money vanishes from the system.

The problem with fractional reserve lending is the leverage. A 10-to-1 reserve ratio means that if the bank issues a $10 loan, the borrower defaults and the borrower's collateral (home, auto, etc.) only fetches $8 on the open market, the bank lost $2, which is more than the bank's cash reserves ($1).

At that point, the bank is insolvent, i,e, its losses exceed its assets.

In credit bubbles, the reserve requirements may reach absurd levels of leverage. At a reserve ratio of 100-to-1, a $2 loss of value in a $100 loan will push the bank into insolvency, as it only held $1 in cash as reserves against the $100 loan.

Reserve requirements and leverage are one set of constraints on new loans; the other constraint is the income, creditworthiness and willingness of the borrower. If households and businesses decide not to borrow more, regardless of the interest rate, then raising or lowering the reserve requirements will have no effect.

This is where the Federal Reserve finds itself today. The Fed is anxious to spark more lending/borrowing, and it has lowered interest rates to near-zero and made it easy for banks to build reserves--two things that in previous eras would have sparked increased borrowing.

But in our debt-saturated, stagnant-income era, the Fed is pushing on a string. Frequent contributor Dave P. explains why with the aid of two of his charts:

Banks can create new money, but only within the limits of the reserve requirements set by the Fed.

This raises the question: what are those reserve requirements? What’s the leverage ratio?

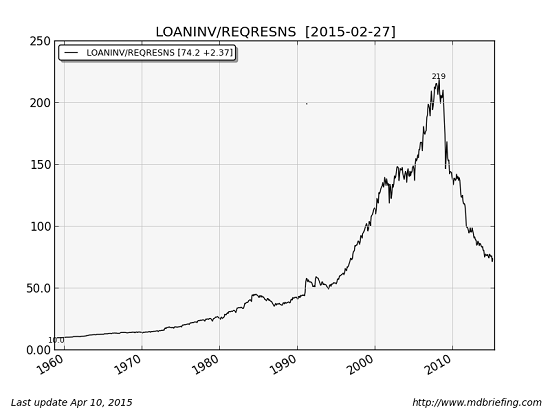

So naturally, I made a chart. This first chart is the total bank credit loan book divided by the reserves required by the Fed for those loans.

(Note: the actual reserves today are quite a bit different - what with the excess reserves and all that.)

The interesting part of this chart is in two places: one in 1960, where the ratio was 10:1, and the other in 2008, where the ratio was 219:1.

The 10:1 ratio is probably where the “money multiplier effect” textbooks were written. Back then it was true.

By 2008, reserve requirements basically didn’t matter. “Go ahead, make whatever loans you’d like, we’ll just drop the reserve requirements in order to facilitate your loan book.”

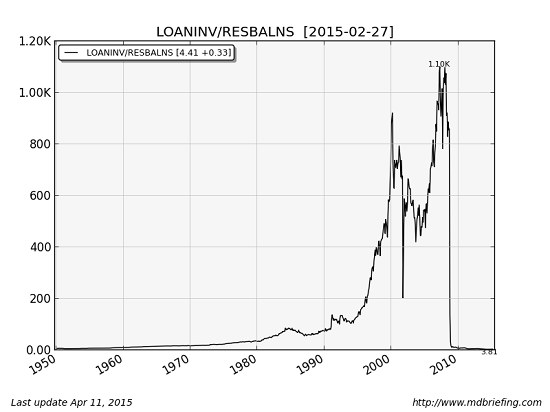

Note: the leverage today isn’t as bad as it looks. The next chart, LOANINV/RESBALNS, loans vs actual reserves, is shocking in its own way. The excess reserves at the Fed have the current effective ratio at... are you ready? 3.8:1. There are $3.81 dollars in loans for every $1 in reserves currently. The Fed is pushing on a string. The truth embodied in the next chart: nobody wants to borrow, so the reserves pile up way, way in excess of requirements.

The first chart: “how we got here.”

The next chart: “the Fed’s attempted fix:” Just expand reserves. That should fix everything. Unless of course borrowers are tapped out. Expanding reserves has worked since 1960. It doesn’t work any more.

RE: the chart of LOANINV/RESBALNS: Yes, the 1100 number at the top means a ratio of 1100:1, loans-to-reserves, which was 5x above requirements at the peak. Hard to believe. “What were they thinking?"

Thank you, Dave, for the charts and explanation. At a reserve ratio of 219:1 at the peak of the 2008 bubble, the tiniest loss rendered lenders insolvent. No wonder the losses unleashed by the subprime mortgage fiasco crashed like a tsunami through the global financial system.

But lowering reserve requirements is no longer generating more borrowing, for two basic reasons: those who might want to borrow are no longer creditworthy due to excessive debt and/or stagnant income, or those who qualify to borrow more are not interested in borrowing more at any interest rate: they are done with debt.

As others have noted, the Fed can push interest rates down and make it easy for banks to loan more money, but it can't (yet) force us to borrow money we don't want or need.

NOTE: Contributions/subscriptions are acknowledged in the order received. Your name and email remain confidential and will not be given to any other individual, company or agency.

|

Thank you, Robert B. ($75), for your stupendously generous contribution to this site-- I am greatly honored by your steadfast support and readership. |